Our Children Need Education Abolitionist

Picture yourself seated in a graduate school classroom listening to a professor at the predominantly white institution proclaim, “Poor black children don’t have books in their homes.” As if I were being pranked, I immediately scanned the room for allies / co-conspirators who would aid me in correcting his ignorance. There was only one person, one Latina sista in the struggle who volunteered to join me in an attempt to address his verbal assault on Black families as my remaining classmates, a sea of emotionless white faces, sat silent as if they were voyeurs who hung onto every word in agreement.

At that moment, what I knew to be true is that my clueless white classmates and/or those with no reference to Black people or our communities, would leave the class believing that his statement was factual. This is when I knew that amongst other acts of resistance, my liberation would prevent me from remaining silent in moments of injustice.

This remark follows more than two decades in spent public schools, where I’ve witnessed a litany of biases against Black students. These offenses include (but are not limited to) the alarming trend of over policing & disproportionate suspensions, the insidious presence of micro-aggressions, the perpetuation of harmful stereotypes, and the harsh realities of racism at the hands of the blatant, the aversive racist and the oh so dangerous/performative “well-intentioned.” Tragically, on any given school day, a Black child can either fall victim to the performative white saviorism or be reduced to total invisibility.

Imagine, spending a career watching students with special needs diagnoses’ having their educational services ignored daily. Their Individual Education Plans (IEPs), uniquely designed to aid them in reaching benchmarks all but disregarded. Lastly, imagine all of this taking place in spaces which are racially segregated, where the use of deficit language to describe Black children is the norm, where poverty is fetishized, where Black excellence is nowhere to be found in the curriculum and students at the lunch tables are self-separated. In these classrooms, Black history begins with the enslaved and only Martin, Rosa and Harriet Tubman are highlighted during the annual Black History Month assemblies. In these classrooms, The Reconstruction Era is taught through the lens of students viewing Gone with the Wind and To Kill a Mockingbird is a pillar in the English class.

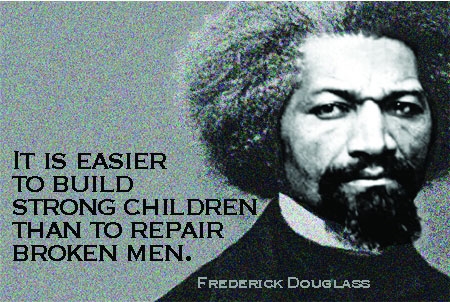

What I know to be true is that Black children need champions and education abolitionists who are willing to step up and be the voice of the voiceless. They need advocates in the homogenous conference rooms where they’re being discussed, where they’re made to be the problem and routinely described using racially coded language (i.e., low SES, Title 1 students, urban, disadvantaged).

From where I sat, for the many years that I’ve witnessed these inequalities with a sense of helplessness that I never intend to experience again. As such, I am committed to being an education abolitionist for Black children. In the truest essence of Harriet Tubman, I am committed to recruiting more advocates as we aim to liberate our children from the shackles of institutional racism and point them towards greatness and not prisons. In the truest essence of Harriet Tubman, I have also come to recognize that silence can be a necessary weapon in unsafe spaces.

In my decolonized world of academia, we speak truth to power with fearlessness. Our children learn in spaces where hiring agents understand that representation matters, and their Black excellence and potential is celebrated daily. Our children need warriors who will show up for them and be the champions they need to stand in the gap to disrupt oppression, right the wrongs, and lead them to success.

Recently, I heard a sister say that her mother told her “If you see me fighting a bear, help the bear.” I felt that in my soul. In that regard, if you see me fighting for our children, stand beside me.

Author:

L.M Johnson, MA, MHC